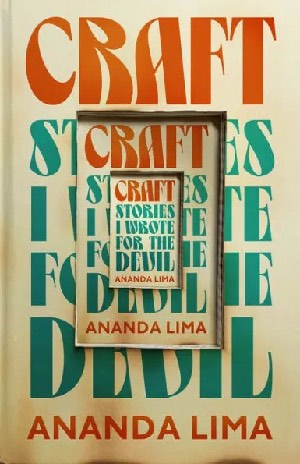

Craft: Stories I Wrote for the Devil

Craft: Stories I Wrote for the Devil is a crafty collection. It is a tapestry of tales that have subliminal links to each other while gleefully playing with meta and the metaphysical. Even before opening the unconventionally structured book, there’s a thematic hint of what’s inside. The brilliant jacket design by Jamie Stafford-Hill informs the reader that author Ananda Lima’s stories which await within are part of a larger whole. Lima incorporates her Brazilian background and time spent in New York City into the into the narratives, often fusing the experiences with phantasmagoria. Any attempt to categorize this holistic amalgamation of yarns is futile. With adroit precision, the volume presents a witty thumbing of the nose at labels and tradition. The prose is engaging and intelligent. And requires a surrendering to the surreal.

Stylistically, the author employs a device that caused me to search for clarification. There are tales that have titles but, either as a prologue or follow-up, there are also untitled narratives that use curly brackets { } centered at the top of the top of the page in lieu of a story title. My internet research revealed: “Curly brackets are used by text editors to mark editorial insertions or interpolations.” An example of Lima’s curly brackets application occurs after a tale titled “Ghost Story.” The top of the page curly brackets is followed by ruminations that include an introspective response to the design of Guggenheim Museum: “She loved how the building literally moved the people around the space. The building was motion, an organism. It was time in reinforced concrete. She looked up. It looked like a flower, the petals splayed in distorted perspective, like a cubist painting, but following a mid-century logic. She was full, bursting, in love. That was how a new place took root inside. Searching for home, she was stretching herself, letting her love expand categories, to fit more in.” This integration of interpolation works well in terms of juxtaposition between a titled story and the more overt personal/biographical reflections which often occur in tales headed by curly brackets.

To state the obvious, Lima leans into the literary. The perception and passage of time is often a philosophical thread. In the tale “Rapture,” the protagonist reflects “I wished I could explain to myself in 1981, and myself now, how time worked. Its mind-boggling speed, even when each day can be slow like a trudge through tar.” In “Porcelain,” there’s the apt observation that “Time was impossible to hold on to without a means to measure it, contain it.” “Porcelain” is a disturbing and poignant tale of loneliness and alienation. Bernard, the emotionally isolated protagonist, is pondering relating a circulating story as a social lubricant, which concerns a man who finds a rat in his toilet: “The man opened the bowl and found the rat was still there and felt paralyzed by the impossibility of those dark gelatinous eyes looking at him. The wet fur was stuck to its head in a way that made it look angry. It moved, gathering itself in a spring of muscle and dark fur. Then it leaped.” The man mentally wrestles with repulsion while also seeing the animal as an entrapped frightened creature. Despite loathing to do so, the man relates that he killed the rodent but mercifully doesn’t describe the process. Bernard would have done things differently: “Bernard would not have killed the rat. He’d have sat with it, on top of the toilet. He would have kept it around until it got tired of him. Bernard wondered how it would feel to have another living thing appearing here just like that.”

Bernard’s sense of being remote from society reflects a recurring motif in the stories. Immigrants who are kept at arms’ length are typical and topical features. The subsequent and unsubtle political subtext that occurs may be abrasive to certain readers, but fortunately it doesn’t beat the subject to death. Such relevance and social commentary don’t bog down the narratives since the writer has a flair for whimsy. That playful panache is most evident in the epistolary story “Idle Hands.” The tale’s title refers to a draft of a story that the author has submitted to a writers’ workshop. The comments elicited from the workshop participants comprise this highly meta narrative, with each “participant” displaying “their” unique voice in critiquing the work. One even mistakenly/uncaringly refers to the story’s author as “Amanda” rather than “Ananda.” Head-spinning surreal yet teeming with relevance for writers, “Idle Hands” is funny and wise.

The Devil is surely in the details in Craft: Stories I Wrote for the Devil. In the book he is depicted as an entity who stimulates creativity, urging the author to delve into personal history and conjure up fiction that is based on experiences and sentiment. The Devil is, in essence, the consummate editor. And muse. He is seductive, coaxing, and invigorating. Appreciative of wit and insightfulness. Before this symbolic collaboration, earlier versions of these stories had appeared in various scholarly/literary publications. Tor books now widens the audience who can experience Ananda Lima’s wonderfully offbeat offerings.