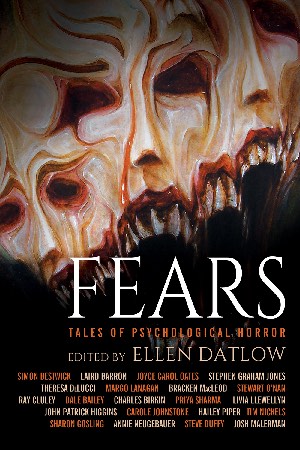

Fears: Tales of Psychological Horror

The supernatural is a mainstay of horror fiction. Yet in the reality of the darkest recesses of our hearts, we know that lots of fears stem from the potential of human perpetrated horrors. Be it the concern of our chances of being gunned down by an anonymous shooter at a public venue or awareness of horrific genocides, fear of dangerous human beings quietly lurks in our subconscious. Editor Ellen Datlow explores this in the aptly named Fears: Tales of Psychological Horror. The anthology contains 21 previously published stories that focus on deadly aberrations of character. Serial killers are well represented, and revenge is a thematic staple in some of the yarns. The four tales that I choose to highlight take such elements to a notable level of interest. And all have clever and/or ironic titles.

“Bait” by Simon Bestwick is the first story in the compilation. It has an Interview with the Vampire, sans vampires, sort of feel to it. The narrator, who has come across a particularly sanguinary murder scene, evaluates the killer: “She stood there, very still. There wasn’t, as far as I could see, a drop of blood on her, not counting the knife and the fingers of one preternaturally white—latex gloved, I realised—hand. Her face was very pale, haloed by her dark hair, and utterly calm, almost like a Madonna. Dark Eyes, studying me.” He winds up going with the efficient murderess to a pub where she sizes him up while chatting about her homicidal history and methodology. She doesn’t disclose the origin of her serial dispatching of odious men, choosing instead to tease with well worn scenarios that may or may not have any truth behind them. He sums up her dispassion thus: “A shark. A machine. A process repeated over and over again, and she didn’t even know why.” At one point, the narrator even posits the theory that she could be an immortal like The Flying Dutchman, following her destiny throughout time. But this gets dismissed as an inebriated notion. Bestwick makes their conversation fascinating. It’s not completely intellectual since the narrator is aware of the inherent peril. Thus, there is an edginess beneath the surface of what appears to be controlled civilized dialogue. “Bait” is short in length yet excellently yields a sustained tension.

The humorously titled “The Donner Party” is predictable in the trajectory of its plot but is highly worthwhile, nonetheless. In a 19th Century universe, the upper crust is presided over by Lady Donner. She belongs to one of the First Families of Society and sets the standards for approbation. Social climbing Mrs. Breen is ascending the ladder of acceptance but makes a major faux pas along the way. It causes her to be ostracized by the elites she admires and be scorned even by her husband. Confused and feeling abandoned, she rejects the ministrations of a footman who tries to assist her to her carriage and storms off: “The blind, heat-struck roar of the city soon enveloped her. The throng pressed close, a phantasmagoria of subhuman faces, cruel and strange, distorted as the faces in dreams, their pores overlarge, their yellow flesh stippled with perspiration. Buildings leaned over her at impossible angles. The air was dense with the creak of passing omnibuses and the cries of cabbies and costermongers and, most of all, the whinny and stench of horses, and the heaping piles of excrement they left steaming in the streets.” Contrast that repugnant imagery with the gentility and refinement that Mrs. Breen gained while basking in Mrs. Donner’s approval: “They were seen making the rounds at the Royal Academy’s Exhibition together, pausing before each painting to adjudge its merits. Neither of them had any aptitude for the visual arts, or indeed any interest in them, but being seen at the Exhibition was important.” Such cultural skewering abounds in writer Dale Bailey’s searing censure of the extremes of upper-class privilege. With “The Donner Party” Bailey powerfully unleashes verbal venom on societal mores and the (at times literal) hunger for status.

What appears to be a story about the horrors of aging and care facilities veers into unexpected territory in Sharon Gosling’s “Souvenirs.” The elderly protagonist must come to terms with his limitations and succumbs to his daughter’s push for him to enter assisted living. He divests himself of the bulk of his belongings, keeping only a remnant of his vast travels. There’s a poignancy to his reaction to this new and final stage of his life: “It was barely five o’clock but the light was already beginning to disintegrate. The faded roses, dead but with their heads still waving aimlessly on their stalks, seemed to him to be a particularly malicious joke.” However, in a jolt of acknowledging his adaptability, he realizes that his past has a place in his present. Falling back on old habits will bring him a demented sense of joy. Three cheers for Gosling for mischievously leading the reader astray.

It’s always fun to read a tale where it’s hard to discern the predator from the prey. In Laird Barron’s “LD 50” that’s the case. The protagonist is a hardcore badass who goes beyond the term “free spirit.” She does an admirably clear-eyed assessment of her attributes: “I composed myself and moseyed around town for the rest of the afternoon. Youngish female and not terribly unattractive, nobody mistook me for a pervert or a weirdo as they would’ve if I’d been some bearded sunbaked dude lurching in off the prairie. People skills, I had them, and most folks were willing to shoot the shit with me as they watered lawns, or washed cars, or slumped in the shade of their porches. I wore my shades and gave everybody a different story, all of them pure baloney.” Her survival skills come from a background of taking risks. A dangerous sexual relationship is just part of it. Barron does a great job in getting inside the skin of the character and in creating a tangible atmosphere. I purposely chose to wait until I finished the tale before researching the meaning of its title. It was the right decision.

Fears: Tales of Psychological Horror is published by Tachyon. The collection is a fine reminder that “The evil that men” and parenthetically women, “do lives after them.”