Happy Turkey Day

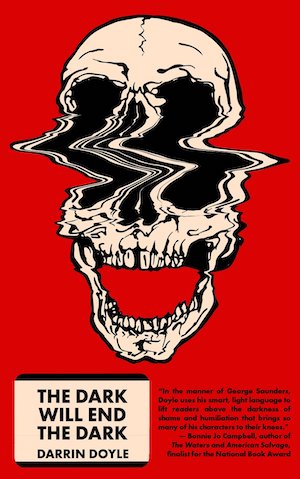

The collection of stories featured in The Dark Will End the Dark by Darrin Doyle display a fondness for the surreal. There’s a sense of reverence for Franz Kafka, most particularly his famous novella “Metamorphosis,” in which the protagonist wakes up transformed into a giant insect. Doyle’s writing also exudes a fondness for the Theater of the Absurd, finding a sort of solace in the comedic aspects of preposterously taxing situations. Reading fifteen tales in this vein can become rather repetitive. Perhaps that’s why I am choosing to focus on one story; a yarn that differs from the rest in terms of more detailed characterization, and more depth in general. “Happy Turkey Day” is a fitting focus for this time of year, although the narrative only briefly references Thanksgiving.

Zeroing in on four male characters who have peculiar surnames or nasty nicknames, the tale asks the Shakespearean question “What’s in a name?” It also delves into insecurities and the dangers of acting upon them. A father and son share the surname Turkey, but neither has endured mockery from it. Both are seeming successes in their respective endeavors: the dad had turned his inherited business into a money-maker, while the son Jonathan is a big man on campus courtesy of his athletic prowess and charisma. Unfortunately, the son has alienated a fellow student by contorting that student’s last name into an obscene joke moniker. Which prompts the recipient of the cruel, crude humor to be reflective: “Why, Claude wonders, do names have to be verbal at all? Language is a faulty system. His name could be a scent in the air, a taste on the tongue’s buds, the flapping of hung sheets undulating in the breeze.” Despite engaging in poetic musings on the topic, this is the underlying issue: “What angers Claude most, though, even more than the hero worship and the numbness to the moniker, is the utter indifference J.T. and his adoring fans display toward their own mortality. Johnny Turkey is king of the blind, duke of the deluded, emperor of the idiot Adonises who are too busy with proms and pep rallies to notice the wild boar crouching in wait around the corner.”

Being ridiculed is particularly hard to emotionally navigate when one is that smart and insightful. But the fourth male in the story’s spotlight is mentally challenged and doesn’t comprehend the cruelty behind the nickname he’s known by: Ronnie Moe, a variation on the word “moron.” Monikers have nothing to do with the younger Turkey’s latent fear of ridicule. When stressed, he suffers from rashes “resembling in color the inside of a watermelon and in texture the scales of a snake.” For a perceived golden boy, this is a weakness: “Jonathan’s main fear is that they will flare up during a game. Word would spread like the rash itself, from person to person, until everyone knew he was a monster.”

Jonathan’s dad also employs the word “monster” as he ruminates upon himself: “When, Winnicott wonders, did I become a monster?” Such self-loathing permits destructive behavior: “He desires other’s pity so he won’t need his own. For this same reason, Winnicott crashes BMWs into trees; he drives the family business into the ground; he blows $1100 a week on blow. His efforts to evoke pity leave his self-hatred intact while compelling no one to feel sorry for him.”

When the four males with the unconventional appellations converge, the destructive aspects of their respective personalities surface with a vengeance. Quirky impulses lead to a deadly dramedy of errors.

Though not as surreal and, therefore, less representative of other stories in this Darrin Doyle collection, I found “Happy Turkey Day” a shrewd ironic tale with finely delineated characters. The bulk of the narratives in The Dark Will End the Dark, a tenth anniversary reprint published by Tortoise Books, emphasize reactions to ludicrously dark circumstances. In contrast, “Happy Turkey Day,” is more propelled by personas than external events. Its 30 pages provide a satisfying deeper dive into how burdensome the absurdities of daily life can be, exemplifying the idiom of a “turkey” sort of day.