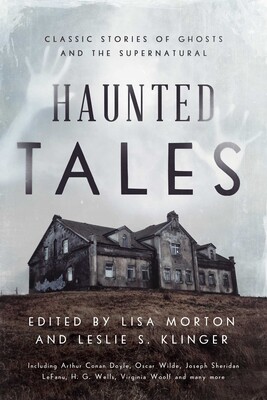

Haunted Tales

Say the term “ghost story” and you have me at hello. Still, I was a bit wary of reading another collection about spooks and the supernatural. The lengthy subtitle of Haunted Tales is Classic Stories of Ghosts and the Supernatural. This reinforced my trepidation since “classic” implies that the tales have been reprinted many times. And indeed, some of the narratives in this compilation do give credence to that inherent supposition. But in addition to my great fondness for ghostly/supernatural short stories, I greatly respect the editors of this anthology. Leslie S. Klinger and Lisa Morton are, individually, extremely thoughtful in analysis and explication. Together, they make a terrific team that deftly dispenses historical and biographical detail. The twenty tales they have selected are well chosen and date from 1838 to 1929. For the sake of brevity, I will discuss only a few of them; ones that impressed me because of their descriptive prowess. While I could go on at length about how Oscar Wilde’s wit devilishly dissects the cultural mores of British and American society in “The Canterville Ghost” (1887) or sing the praises of the always wonderful E.F. Benson represented here by “The Bus Conductor” (1906), I’ve opted instead to look at works by two women authors as well as a story co-written by a mother and son writer duo. Plus, there is a goody by Algernon Blackwood that is too creepy to ignore, which features passages that struck me as defining the overall tone of the anthology.

Blackwood’s tale “The Kit-Bag” (1908) discusses how hard it is to understand the stages of fear: “It is difficult to say exactly at what point fear begins, when the causes of that fear are not plainly before your eyes. Impressions gather on the surface of the mind, film by film, as ice gathers on the surface of still water, but often so lightly that they claim no definite recognition from the consciousness.” The protagonist of the narrative is a barrister who defended a murderer at trial, resulting in a verdict of insanity. Thinking his scheduled skiing vacation will help shake away pesky images of the killer, the young attorney finds that nagging thoughts persist, and finally culminate during packing for the trip. Blackwood eloquently distills: “Unpleasant, haunting memories have a way of coming back to life again just when the mind least desires them—in the silent watches of the night, on sleepless pillows, during the lonely hours spent by sick and dying beds.”

Amelia B. Edwards, like Algernon Blackwood, has frequently been anthologized. Her “The Phantom Coach” (1864) is a staple in reprints of supernatural fiction. And so it should be. Edwards was nicknamed “the godmother of Egyptology” because of her interest in ancient Egypt. Although “The Phantom Coach” doesn’t touch upon that part of her life, it does somewhat address a different aspect of it. She was a member of a previous LGBTQ community. Her sexual orientation fits well into the realm of horror fiction, where the point of view of an outsider is often employed and handled with sensitivity. In this passage from the plot, the narrator is frighteningly outnumbered by those who recognize that he isn’t one of them: “A pale phosphorescent light—the light of putrefaction—played upon their awful faces; upon their hair, dank with the dews of the grave; upon their clothes, earth-stained and dropping to pieces; upon their hands, which were the hands of corpses long buried. Only their eyes, their terrible eyes, were living; and those eyes were all turned menacingly upon me!” It’s a shocking twist on the convention that the majority rules. In this case it is a living person who is the minority, outnumbered in a coach full of the judgmental and hateful dead.

“The Story of the Spaniards, Hammersmith” (1898) was a first for me. I had not read anything by Hesketh Vernon Prichard or by his mother, Kate Prichard. In fact, I had never even heard of them. Under the pseudonyms of H. Heron and E. Heron, the writing team was published in popular journals and known for their stories featuring a Spanish Robin Hood-esque character. Through J.M. Barrie, who was part of the Prichard circle of writers, they were introduced to a publisher who wanted them to write a series of stories which were labeled/marketed as “Real Ghost Stories,” much to the distress of the authors. Their creation of Flaxman Low, “the world’s first detective specializing in psychic matters,” was inspired. Low’s name, like his creators’, is a pseudonym. The Low pseudonym disguises the identity of an esteemed Victorian scientist, and former university athlete, who applies a scientific approach to his occult studies. The story reprinted in Haunted Tales is the first in the series of twelve Flaxman Low yarns. In this passage, Low has an uncomfortable up-close-and-personal rude awakening from slumber: “Next he was aware that the thing on the bed had slowly shifted, and was gradually travelling up towards his chest. How it came on the bed he had no idea. Had it leaped or climbed? The sensation he experienced as it moved was of some ponderous, pulpy body, not crawling or creeping, but spreading! It was horrible! He tried to move his lower limbs, but could not because of the deadening weight.”

Another story and author were introduced to me via Pegasus Books’ Haunted Tales. G.G. Pendarves was, during the 1920s and 1930s, a popular writer of short fiction whose work was published in Weird Tales pulp magazine. In “The Laughing Thing” (1929), she explores the malign side of laughter. While usually associated with mirth, laughter can also be cruel; an expression of ridicule and/or vengeance. At the beginning, the narrative seems to be headed on a predictable moral comeuppance trajectory. Then something more profoundly woeful sets in, the foreboding gets a chilling change of focus. The prose of Ms. Pendarves begs to be read aloud. And I didn’t even try to stop myself from doing just that with this atmospheric excerpt: “The woods grew darker with every passing day, despite the thinning of the leaves. The autumn mists which lay white and cloudlike in the valleys of the surrounding country, drifted in among the trees on the Tareytown estate like gray, choking smoke, damp and rotten with the breath of decay, shutting out the sunlit earth beyond, and the clear skies above, rolling up around the house with infinite menace and gloom.”

Haunted Tales made me glad that I overcame my initial wariness about reading another “classic stories” anthology. There were intriguing tales that I hadn’t savored in the past, and the ones that I had read before felt like visiting with old friends. Leslie S. Klinger and Lisa Morton don’t disappoint.