In the Mad Mountains

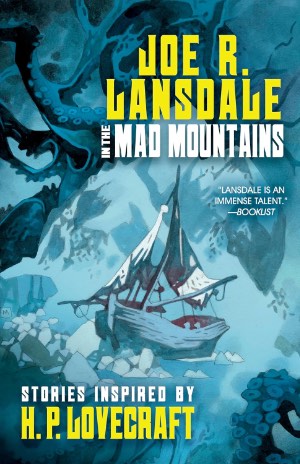

Joe R. Lansdale is a treasure. His writing in and out of the horror field is a delight to read. He is quite a chameleon, not only in his ability to shift from genre to genre, but in terms of style and literary voice. His abundant talent is on full display in In the Mad Mountains: Stories Inspired by H.P. Lovecraft, published by Tachyon. The handsome trade paperback features eye-catching cover art by Mike Mignola and cover design by Elizabeth Story, along with interior design by John Coulthart that has a nice geometric Lovecraftian feel. All eight stories in the collection were previously published, the oldest in 2009 and the most recent in 2015. Each features an insightful introduction by Lansdale. As is my routine with short stories, I chose a fraction of the offerings for focused discussion.

“The Bleeding Shadow” is a tale told in American Noir Crime mode, with a Southern drawl. It begins: “I was down at the Blue Light Joint that night, finishing off some ribs and listening to some blues, when in walked Alma May. She was looking good too. Had a dress on and it fit her the way a dress ought to fit every woman in the world. She was wearing a little flat hat that leaned to one side, like an unbalanced plate on a waiter’s palm. The high heels she had on made her legs look tight and way all right.” Shades of the character Velma in Raymond Chandler’s 1940 novel Farewell, My Lovely who is described as “Cute as lace pants.” Because the story’s cast of characters is African American it’s conceivable that author Walter Mosley’s 1990 Devil in a Blue Dress, which introduced hardboiled detective Easy Rawlins, may also have been an influence. But it is Lovecraft’s inspiration that drives Landsdale’s narrative: “There was something inside the music; something that squished and scuttled and honked and raved, something unsettling, like a snake in a satin glove.” Unearthly music is a motif derived from Lovecraft’s “The Music of Erich Zann” (1921.) That fusing works remarkably well in a setting that would have unnerved the notoriously racist Lovecraft. I sensed that Lansdale was aware of that delicious irony, and perhaps Victor LaValle who wrote the superb novella The Ballad of Black Tom (2016), had read “The Bleeding Shadow” (published in 2011) and recognized the possibilities. LaValle’s novella was a riff on Lovecraft’s “The Horror at Red Hook” (1925) from the point of view of an African American man.

Race relations is certainly a theme in Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), another work that gets a Lovecraftian spin in In the Mad Mountains. “Dread Island” is narrated by Huck. In Lansdale’s able hands, the voice reads like pure Twain: “Civilizing someone meant they had to go to jobs; and there was a time to show up and a time to leave; and you had to do work in between the coming and leaving. It was a horrible thing to think about, and yet there I was with shoes on. The first step to civilization and not having no fun anymore.” Throw in a couple of staples of African American folklore from the slavery South, Brer Rabbit and the Tar-Baby, mix in with the Lovecraft Cosmos and you have one raucous and splendidly preposterous story. How clever of Lansdale to have Huck and his cohorts refer to Cthulhu as “Cut Through You.” Folksy and sensical.

It seems like Lansdale revels in the challenge to achieve the tone and style of other writers while incorporating Lovecraftian sensibilities. With “The Gruesome Affair of the Electric Blue Lightning,” he creates an Edgar Allan Poe parody starring Poe’s C. Auguste Dupin. In it, a simian similarity to the chimp in Dupin’s debut in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841), is creating havoc…and hybrid creatures: “On a tilted board a nude woman—or a man, or a little of both, was strapped. Its head was male, but the rest of its body was female, except for the feet, which were absurdly masculine.” Along with the phrase “absurdly masculine,” I am fond of this musing expressed by Dupin’s chronicler: “The end of the cosmos and our world as we know it is of considerable concern, of course, but no reason to abandon manners.”

Lansdale’s sense of whimsy is well known. It is easy to fall back on the simplistic sardonic stereotype, but his sheer range belies that. “The Tall Grass” could be considered a tutorial on how to write disconcerting images. Consider: “A split appeared in their faces where a mouth should be, but it was impossibly wide and festooned with more teeth than a shark, long and sharp, many of them crooked as poorly driven nails, stained in spots the color of very old cheese. Their breath rose up like methane from a privy and burned my eyes.”

In his introduction to the collection, Lansdale states that he’s not a fan of Lovecraft’s writing: “It always seemed as unnecessarily difficult as trying to remove a Himalayan snowbank with a garden trowel and a bucket of hot water.” Later he expounds on Lovecraft’s strength: “He had a vision so strong that it leapt over the massive walls of sometimes-unintelligible prose and entered into the human consciousness as if those alien entities might actually exist.” In the Mad Mountains at times pokes fun at the rococo excesses inherent in the Lovecraftian universe, but ultimately displays an appreciative understanding of Lovecraft’s immense contribution to horror fiction. The often-irreverent Joe R. Lansdale bestows a reverence that is uniquely his own.