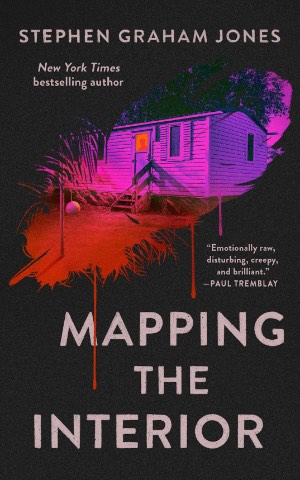

Mapping the Interior

Writer Stephen Graham Jones has quite a following. He is highly regarded by reviewers and readers for his prose and application of his Native American background into his works. His novella Mapping the Interior helped to put him on the map, so to speak, courtesy of a Bram Stoker Award in the category of Long Fiction. First published in 2017, the Tor Publishing Group has just reissued it under its Nightfire banner. That gave me the opportunity to read the book for the first time and rectify a past omission. In its 96 pages, there is much psychological and sociological insight about American Indian culture. But at its heart, the narrative is a horror story about the complexities of family relationships: Unhealthy cycles can be unbreakable, and the past does haunt.

The tale’s narrator, known as Junior, starts being haunted at the age of twelve. His dad had died when Junior was four years old, leaving the kid to learn to help care for his mentally disabled younger brother, relieving some burden for their beleaguered mother. When the father’s apparition first appears to the sixth grader, the boy sees his dad in the regalia of a tribal dancer, something the man had dreams of being. The precocious child notes: “In death, he had become what he could never be in life.” Junior later surmises that his father required certain elements to physically manifest: “When you come back from the dead, you’re a spirit, you’re nothing, just some leftover intention, some unassociated memory. But then, then what if a cat’s sneaked into a dark space like this, right? What if that cat comes here to die, because it got slapped out on the road or hit by an owl or something, so it lays back in the corner to pant it out alone. Except, in that state, when it’s hurt like that, when this cat isn’t watching the way it usually does, something else can creep in. Something dead.” That passage is followed by this short paragraph: “It’s the injury that opens the door, I knew. The corruption.” The language in the longer of those connecting quotations is notable for its conjecturing tone, the questing for affirmation by asking “right?” of a nebulous someone. With the brief follow-up paragraph, the words “I knew” indicate that Junior has attained a semblance of certainty.

Yet that impression of certitude doesn’t provide comfort when it appears that Dad has an agenda to become more corporeal and permanent. This kicks into play Junior’s protective instincts, causing him to again question: “Even if he wasn’t dead or a ghost, he would still be our dad, wouldn’t he? What could a sixth-grader and a third-grader and a mom do against a dad?” The rhetorical queries in the two sentences are again immediately followed with a conclusion: “When they’re drinking, you can slip away, hide. But the only thing Dad was going to be drunk on, it was us.”

As the novel approaches its end, Junior is a father in his forties and echoing much of his erratic dad’s familial irresponsibility. In a chilling display of the biblical quotation, “the sins of the fathers,” Junior rekindles the harm that has been done and will continue being done. While some of the actions seem metaphorical, they are nonetheless powerful. Employing an economy of words, author Stephen Graham Jones spoke volumes. Thanks to Nightfire for sending me a review copy of this reprint edition of Mapping the Interior. Doing so offset my missing out on this impressive novella when it was first published.