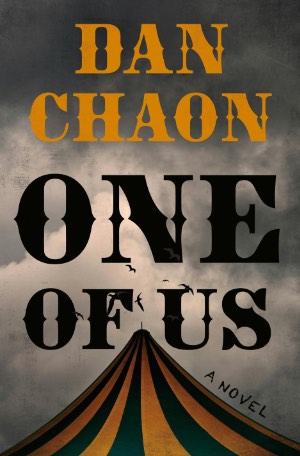

One of Us

“Weird” is a complimentary word in the lexicon of horror fiction. One of Us, written by Dan Chaon is one of the weirder books I’ve read. It’s very literary and cinematic in allusions; I can easily fantasize a film adaptation sumptuously directed by Guillermo del Toro. The narrative largely unfolds in 1915, a time when the world was in flux and keen on cultural oddities. Carnivals and sideshows satiated the appetite for the bizarre. Author Chaon employs this universe to unveil an outlandish narrative that is tantalizingly peculiar. At times the novel is heartbreaking. In other instances, it is hilariously absurd and facetious, chock full of references warped by the writer’s droll sense of humor. Like the freakish world it depicts, One of Us is idiosyncratic and eccentric.

The story is centered on Eleanor and Bolt, orphaned twin siblings who are approaching puberty. They can mindread each other’s thoughts, which helps them survive brutal circumstances, not the least of which is escaping maniacal Uncle Charlie. Charlie is a charlatan. His claim of being their late father’s brother is bogus, and lying is not the least of Charlie’s sins; he is a totally bonkers serial killer. His Uncle Charlie moniker is author Chaon’s allusion to another serial killer: Uncle Charlie in the Alfred Hitchcock film Shadow of a Doubt. There are many such in-joke references scattered throughout the novel. I noticed that the character of Eleanor, like the Eleanor in the 1961 film The Haunting (based on Shirley Jackson’s novel The Haunting of Hill House), is deemed responsible for a shower of clumps of dirt/stones. And then there’s Billy Bigelow who operates the carousel in One of Us, just happening to have the same name as the carousel worker in Rodger’s and Hammerstein’s musical Carousel. Apparently, Chaon has a certain fondness for musicals, since the state of Iowa is described much as depicted in the musical The Music Man, with its “gazebos and marching bands and barbershop quartets.” It’s quite likely that there are other such amusing attributions that I didn’t spot in a single reading.

In the author’s note which appears at the end of the book, Chaon acknowledges the influences that helped form the narrative. The most obvious being director Tod Browning’s 1932 film Freaks, and two of Ray Bradbury’s most famous works, Dark Carnival and Something Wicked This Way Comes. It is also stated that “Thomas Tryon’s novel The Other was also a big influence — as it has been since I first read it when I was thirteen.” No question about it, Dan Chaon has terrific taste.

In addition to fine artistic taste, the author exhibits artistry through prose. Deliberate word choice is important when conveying emotion in writing, as is reflected by this rumination on verbal expression: “There should be a word for that cosmic deflation you feel when your whole heart is singing with joy and anticipation, when you are most full of childlike hope and delight, and then the person you love most in the world says something scornful.” Distilling the deterioration of the closeness of Eleanor and Bolt, that rumination has a resonance that extends beyond the printed page. Bolt is the accessible twin, far more affable than his sister who alienates others through her overt mistrust of them. The sideshow performers are accustomed to being thought of as off-putting, and want to believe that Eleanor is capable of seeing herself as a member of the tribe. For Dr. Chui, a seven-foot-tall male of Chinese descent with a horn protruding from his head, inclusion has its pros and cons: “He feels relatively safe here, though he is aware as he walks the circumference of the carnival that he is also pacing along the wall of the zoo’s enclosure. Protected and yet trapped. Included and collected.”

Indeed, Mr. Jengling, the founder of the Emporium of Wonders that produces the traveling carnival, is a collector. He collects relics that can most delicately be described as biological inconsistencies, and seeks out beings shunned by society due to being different in aspect. Jengling dispenses sympathy for such beings in a bountifully theatrical manner, assuming the role of benign and nurturing father figure. The most needy of tending is young, prophetic Rosalie. She is damaged on many levels, including being physically distorted by the twin sibling she absorbed when they were in the womb. The fetus now resides in the back of Rosalie’s head, and is not pleasant to behold, as is evident by this description: “And then drawing closer, she saw that the protrusion was a sort of face, an infant-sized head, fused, half-submerged in the larger head of its host. Its bulbous, almost amphibious eyes were closed but they scoped slowly under the thin, pin-veined eyelids; its nostrils flared as if it tried to take in breath; its lips moved as if it dreamed of suckling.”

As evident from that passage, shudder inducing imagery is one of the author’s strengths. Another quote that made me revel in revulsion is: “His soul is like a helix strip of yellow flypaper in a butcher shop, upon which dozens of black, squirming horseflies are trapped, their legs grasping and stuck wings flexing.” A wonderfully conceived simile that expertly conveys god awfulness.

To reiterate, One of Us, published by Henry Holt and Company, is a very weird novel. In the best sense of weird. Like a carnival ride that elicits laughter and thrilling scares, the narrative succeeds on many levels. Parenthetically, the book’s title has multiple meanings, which is yet another example of Dan Chaon’s literary dexterity.