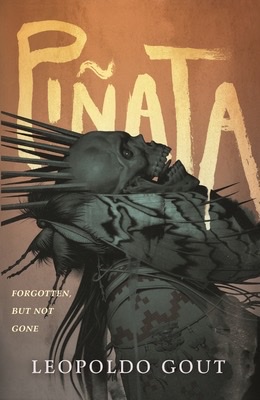

Piñata

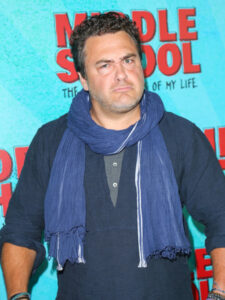

William Peter Blatty’s 1971 novel, The Exorcist, was a game changer for horror fiction. The often-emulated book was the gold standard for narratives that ventured into the realm of demonic possession. There was a deluge of Exorcist wannabes. Then the craze, as all crazes do, came to a lull. With the release of Piñata this month, there came a quiver of anticipation. The novel by Leopoldo Gout was marketed as a classy take on the subgenre. There’s the striking jacket illustration by João Ruas, and much ado was made about the thematic gravitas. Indeed, the plot covers complex indigenous folklore, the extremely important acknowledgement of culture erasure, perils of illegal border crossing, Mexican cartels, and corruption: checking all the boxes for regional social commentary. And for those who prefer to skim over all that weighty relevance in favor of more traditional staples of horror, there’s ample blood and gore as well as the lurking grimness of an Armageddon. The book is certainly ambitious in scope. Unfortunately, ambitiousness in and of itself, doesn’t compensate for the lack of strong writing. Author Leopoldo Gout, whose resume includes being a television producer, writer, and showrunner, is likely intent on selling the novel as a potential screen media project. There are shorthand approaches in conveying the material: a sketchiness with the characterization, a choppiness in the pace that seems more in harmony with rapid fire editing often seen onscreen. And there are questionable word choices that come across as perfunctory; sufficient for conveying a quick mental picture in lieu of delving deeper.

The plot centers on Carmen Sanchez, a single mother of Mexican descent who dwells in New York. A work assignment in Mexico, overseeing the transition of a cathedral into an upscale hotel, gives her the opportunity to provide her adolescent daughters with a smidgen of their ethnic heritage. What ensues is a cultural crash course that culminates in going mano a mano with mythological demons, legions of malevolent black butterflies and, rather than a plague of locusts, confrontations with crickets of abnormal size and lethal agendas.

Carmen’s reactions to these unanticipated challenges reaches a crescendo when it becomes apparent that her once gregarious younger daughter Luna is now a vessel controlled by an evil entity. The mother’s response to the situation, as expressed in this passage, seems a tad odd: “Hundreds of bugs flew around the room, smacking against the door and flying past Carmen’s head as she opened it wider. The light from behind her fell on the foot of Luna’s bed upon which the piñata sat, throbbing and glimmering wet in the faint light that leaked in. Carmen was entranced by its terrible appearance.”

She was “entranced”? Perhaps the author meant to indicate that Carmen was “transfixed.” There’s a disconnect that occurs from reading words that don’t gel. Another jolting verbal fumble occurred while reading an unusual application of the word “cacophony.” As Luna engages in the overused genre device of kids doing weird drawings, there’s this description: “The page was drowning under the cacophony of figures.” The imagery struck me as strange, since cacophony was imbedded in my brain as being aural/auditory rather than visual/visible. A Thesaurus visit validated my mindset. I wondered if the author was attempting to be poetic, or maybe there was a more facile explanation. He might simply like the word “cacophony,” since he drops it again in: “A breathless cacophony of tortured souls howled like the wind in his head.”

The novel’s abundant social commentary elements are an appeal for relevance. But relevance gets superseded by heavy-handedness when the writing is formulaic. Harkening back to William Peter Blatty who, like Leopoldo Gout, could be referred to as a creative “Hyphenate.” It’s conceivable that Blatty is a role model for Gout: someone who worked in various aspects of show business and wrote a fabulously successful novel concerning a possessed girl. Then follows up with winning an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, his fame in two artistic fields cemented. It is a lofty ambition for any writer. Piñata won’t reach such heights. Rather it is an example of the Oscar Wilde quote, “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.”