Thanksgiving: A Retro Review

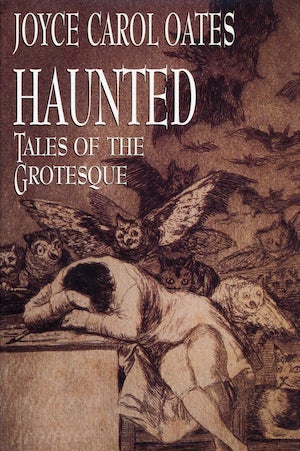

The Christmas ghost story is a component of horror fiction. Knowing that made me wonder about ghost/horror stories pertaining to Thanksgiving. Did such things exist beyond the standard Thanksgiving non-fiction anecdotes of a party going disastrously awry, or an accident involving a frozen turkey? I turned to the Internet and found AI suggestions regarding slasher movies that seize upon various holidays, Thanksgiving included, for subtext. And was also guided to regional folk tales that purportedly took place on the day. Digging deeper, I happened to find a reference to a Joyce Carol Oates short story that had the title “Thanksgiving.” I tracked it to a collection of her stories published by Dutton in 1994, entitled Haunted: Tales of the Grotesque. Originally published in Omni magazine in December 1993, the 12-page narrative is highly disturbing. At once revolting and mesmerizing, it is a bizarre coming-of-age tale that has a chilling resonance in today’s world of making do with what’s at hand.

Before delving into the story itself, let’s discuss definitions. Author Oates in the afterword to the collection elaborates on what constitutes “tales of the grotesque.” In terms of cinematic references, she writes “The grotesque is the hideous animal-men of H.G. Wells’s The Island of Dr. Moreau, or the taboo-images of the most inspired filmmaker of the grotesque of our time, David Cronenberg (The Fly, The Brood, Dead Ringers, Naked Lunch)—that is, the grotesque always possess a blunt physicality that no amount of epistemological exegesis can exorcise.’

She goes on to acknowledge Edgar Allan Poe’s huge influence on what is known as “the grotesque” in horror literature. In horror, Oates expounds, there is an imperative to elicit a response on a visceral level: “One criterion for horror fiction is that we are compelled to read it swiftly, with a rising sense of dread, and so total a suspension of ordinary skepticism, we inhabit the material without question and virtually as its protagonist; we can see no way out except to go forward. Like fairy tales, the art of the grotesque and horror renders us children again, evoking something primal in the soul.”

With “Thanksgiving” Oates captures in abundance the criterion she discusses. The narrative concerns a thirteen-year-old girl who is thrust into addressing a universe that far exceeds the trials of puberty. The circumstances that perpetuate her headlong adjustment into surreal realities are purposely vague, and not pertinent to the plot. All we, the readers, know is that the girl’s mother is indisposed in some way, and unable to shop for Thanksgiving. The girl’s father initiates the trip to an A&P market, where he and his daughter will buy the food necessary for the holiday. Their surveying of the store depicts an apocalyptic atmosphere that is stunningly rendered: “Next, the meat department. Where we had to get our Thanksgiving turkey, if we were going to have a real Thanksgiving. This section, like the frozen foods section, seemed to have been badly damaged. The counters spilled out onto the floor in a mess of twisted metal, broken glass, and spoiling meat—I saw chicken carcasses, coils of sausage like snakes, fat-marbled steaks oozing blood. Here too the smell was overwhelming. Here too roaches were scuttling about.”

As the girl adjusts to what’s available, she finds another venue to search for a suitable turkey: “The opening was like a tunnel into a cave, how large the cave was you couldn’t see because the edges dissolved out into darkness. The ceiling was low, though, only a few inches above my head. Underfoot were puddles of bloody waste, animal heads, skins, intestines, but also whole sides of beef, parts of a butchered pig, slabs of bacon, blood-strippled turkey carcasses, heads off, necks showing gristle and startingly white raw bone.” Such off-putting imagery is neutralized by writer Oates, when followed by the girl’s recollection of culinary normalcy: “All my life that I could remember up to then, helping Mother in the kitchen, I’d been repulsed by the sight of turkey or chicken carcasses in the sink: the scrawny headless necks, the loose-seeming pale-pimpled skin, the scaly clawy feet. And the smell of them, the unmistakable smell.”

The girl quickly follows this up with the remembrance of how cooking the loathsome dead bird transforms it into something succulent: “Spooning stuffing rich with spices into the bird’s scooped-out body, sewing the hole shut, basting with melted fat, roasting. As dead-clammy meat turns to edible meat. As revulsion turns to appetite.” What an amazing summation of food preparation: zoning in on the grisly aspects that will transform to delectability.

Earlier I referred to “Thanksgiving” as a coming-of-age story, and I stand by that. The teenaged girl is forced to reckon with a ghastly situation, adapting by applying what she’s learned from youthful observation. Unearthing this tale about our November feast day made me thankful. Grateful that Joyce Carol Oates wrote a tale about a traditional holiday, one fraught with innate tensions and pressures, and superbly amplifying the cataclysm potential to a horrific level. The story’s protagonist revels in riding the wave of the repugnant and achieving small victories. Gory and fittingly grotesque, “Thanksgiving” satiated my appetite for holiday horror.