The Apple Tree: A Retro Review

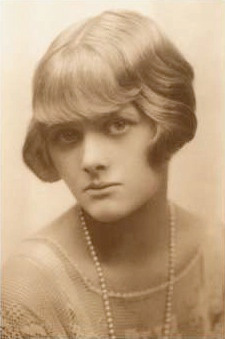

Were you aware that the Society for the Study of The American Gothic has pointed out that January is International Gothic Reading Month (IGRM)? It was news to me. I looked at the suggested reading list that corresponds to the observance and while I questioned some of the selections being labeled Gothic, there was no quibbling about the inclusion of Daphne du Maurier’s quintessentially Gothic novel Rebecca. The celebrated author was renowned for creating suspenseful narratives in which the central character is consumed by compulsion. Often her driven-to-distraction protagonist is female, but in the case of “The Apple Tree” the central figure is a man. A man who becomes obsessed with a tree. As in Rebecca, a dead woman dominates the impulses of the principal character, thus propelling the plot.

Du Maurier brilliantly begins the narrative by making the protagonist appear to be a sympathetic browbeaten husband, whose wife has been dead three months. The widower is initially depicted as an emotionally abused spouse, who was wed to a manipulative martyr. An aging apple tree in the orchard of his property reminds him of the negative qualities of his dead wife: “He went on staring at the apple tree. That martyred bent position, the stooping top, the weary branches, the few withered leaves that had not blown away with the wind and rain of the past winter and now shivered in the spring breeze like wispy hair; all of it protested soundlessly to the owner of the garden looking upon it, ‘I am like this because of you, because of your neglect.’”

An affinity for the widowed man is further established when he ruminates about his unhappy marriage and subsequent disengagement: “So they lived in different worlds, their minds not meeting. Had it always been so? He did not remember. They had been married nearly twenty-five years and were two people who, from force of habit, lived under the same roof.” This is a potentially relatable situation that humanizes the protagonist. Du Maurier, a superb literary trickster, then delivers an unexpected reveal. She cleverly discloses that the beleaguered husband is a blatant male chauvinist, as evidenced by his thoughts on matrimony: “The ideal life, of course, was that led by a man out East, or in the South Seas, who took a native wife. No problem there. Silence, good service, perfect waiting, excellent cooking, no need for conversation; and then, if you wanted something more than that, there she was, young, warm, a companion for the dark hours. No criticism ever, the obedience of an animal to its master, and the lighthearted laughter of a child.” Such sentiment is abhorrent on so many levels, including racial stereotyping, that discussing it further would give way to belligerence. Du Maurier, with that penetrating passage, expertly shifts the reader’s charitable view of the husband. At first, he seems an afflicted victim of an unhappy alliance, haunted by the memory of his wife’s emotional abuse. Then, another dimension is added: he may well be deserving of the mental torment the tree elicits.

His manic fixation on the tree infiltrates all aspects of his life, and he blames the tree for any disruptions or discomfort: “And whichever way he turned his chair, this way or that upon the terrace, it seemed to him that he could not escape the tree, that it stood there above him, reproachful, anxious, desirous of the admiration that he could not give.” From a broken branch used for kindling, which emits a noxious odor only to his nose, to the flavor of its fruit which is repulsive solely to his taste, the tree and the protagonist have what could be construed as an antagonistic relationship. It mirrors the widower’s perception of his marriage and asks the question: Is husbandly guilt the crux of it all, or is the ghost of the wife literally embodying the tree?

Du Maurier’s narrative indeed abounds with ambiguity, as is illustrated by this masterful sentence: “And the tree itself, humped, as it were, in pain, and yet he could almost swear, triumphant, gloating.” Originally published in 1952, and set in post-World War II rural England, “The Apple Tree” is a splendid example of macabre Gothic fiction. Daphne du Maurier (1907-1989) had a penchant for writing works that were spellbindingly immersive. Heady with atmosphere and menace, her fiction in the Gothic mode still enthralls.