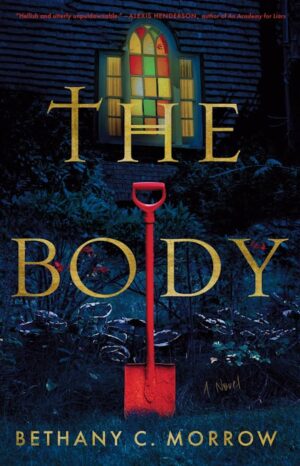

The Body

My first reaction after finishing The Body by Bethany C. Morrow was that the novel’s themes could be simplistically distilled in two words: infidel and infidelity. Mavis, the protagonist in the narrative, is familiar with infidelity in her sexual relationships. And in the congregation led by her judgmental and controlling parents, she is perceived as a religious infidel. Deeply embittered by such experiences, Mavis isn’t the most likeable of characters. She is, however, extremely introspective and expressive. This renders her accessible on an intellectual basis. For psychological self-preservation, she is the architect of a precariously structured emotional edifice. Thus, Mavis is already on shaky ground when the supernatural intrudes and erodes the foundation. The reader’s concern for her becomes heightened courtesy of author Morrow’s fine integration of interpersonal instabilities with cabalistic calamity.

Mavis’s Black cultural identity is tied to her parents’ congregation celebrity: “The daughter of faith community pillars who moonlighted as marriage counselors” she is therefore viewed as a blessed nepo baby. She doesn’t, however, conform to the lofty congregational standards and bridles at her mother’s use of guilt as a manipulative device. Though Mavis does accept the indoctrination that holy matrimony should be her goal. Being married makes one acceptable as well as accepted: an ensemble rite of passage that requires communal participation. The adage about “when you marry someone, you’re also marrying their family” is taken to the max with Mavis’s nuptials. The extended family includes her parents’ congregants, and all present at the ceremony take the marriage vow along with the bride and groom: “It was a well-wishing. An expression of approval. A kind of permission to complete the couple’s vow.” For Mavis, the pact of loving and honoring a spouse until death has horrifying reverberations and ramifications.

Beginning with a car collision that kills another driver, Mavis begins experiencing bizarre assaults. The attackers behave like automatons, hellbent on harming her and those who shield her. The assailants themselves aren’t cognizant of their ferocious aggression: “When the stupor subsided, they had no idea what they’d done. They could attack and maim—they could kill—and they would return to themselves, their conscience clear. Even if their lives were ruined.” In trying to make sense of what is happening, the chronic bitterness is embraced: “For four days people had been trying to kill her, and somehow the onus was on her not just to survive but to investigate their evil. To search for a way to blame herself for their behavior. It was the story of her life.”

Indulging in self-pity is not admirable, and Mavis is not a particularly admirable character. But that doesn’t make her a less than interesting character. She can mutilate an antagonist in a graphically depicted fight and execute retribution on a romantic rival with a carefully conceived trap. The antagonisms she harbors drive her behavior; she has strived for individuality, but her esteemed mother’s shadow looms large. The battle of wills is both literal and allegorical. Grappling with guilt is part of Mavis’s heritage and emotional baggage. The personified manifestations of that guilt are quite spooky.

The Body, published by Nightfire, is an ambitious novel that takes a risk with how readers will respond to a less than sympathetic protagonist. Author Bethany C. Morrow mostly succeeds in making Mavis’s actions appear comprehensible but, as in the case with many works in horror fiction, motivations get muddled in service of plot advancement. Overall, I was satisfied with the book and look forward to reading more of Morrow’s writing in the genre.