The Night Before Christmas: A Retro Review

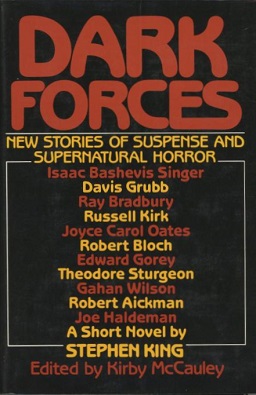

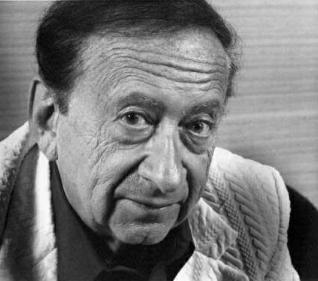

Horror fiction icon Robert Bloch (1917-1994) had an often-quoted quip: “I really have the heart of a small boy. I keep it in a jar on my desk.” Indeed, Bloch had a deliciously deviant sense of humor. Irony permeated his writings, and the ending of his short story “The Night Before Christmas” exemplifies Bloch’s penchant for twisted wit. Originally published in the seminal anthology Dark Forces edited by Kirby McCauley in 1980, the tale remains shocking and consummately Blochian.

The narrative is told in retrospect by an artist in Los Angeles who receives a commission to paint a portrait. Although reluctant to engage with the shipping magnate who requested his services, the artist acquiesces to a meeting: “I remember driving along Coldwater, then making a right turn onto one of those streets leading into the Trousdale Estates. I remember it very well, because the road ahead climbed steeply along the hillside and I kept wondering if the car would make it up the grade. The old heap had an inferiority complex and I could imagine how it felt, wheezing its way past the semicircular driveways clogged with shiny new Cadillacs, Lancias, Alfa-Romeos, and the inevitable Rolls. This was a neighborhood in which the Mercedes was the household’s second car.” Bloch’s expressive prose transports the reader to an imposing affluent area of a teeming metropolis. The contrast between the protagonist’s vehicle and the luxury cars reveals not only an income discrepancy, but an ensuing sense of humiliation. He likens himself to his car with the phrase “I could imagine how it felt,” after attributing “the old heap” with “an inferiority complex.”

The upscale ambience continues once inside the tycoon’s abode, where the narrator meets his potential employer. While his anticipated antipathy towards the rich man comes to fruition, another of the protagonist’s expectations gets jolted by the subject of the painting. The artist erroneously assumed the commissioned portrait would be of the magnate; instead, the picture is to be of the wealthy man’s comely wife. An instant mutual attraction between artist and model seals the deal. The painter accepts the commission and rationalizes about the inevitability of it all, employing metaphors from Greek mythology (he had already pegged the tycoon as a prototypical half-bull Minotaur) and fairy tales: “Cinderella had wanted out of the kitchen and took the obvious steps to escape. She lacked the intellectual equipment to find another route, and in our society—despite the earnest disclaimers of Women’s Lib—Beauty usually ends up with the Beast. Sometimes it’s a young Beast with nothing to offer but a state of perpetual rut; more often it’s an aging Beast who provides status and security in return for occasional coupling. But even that had been denied Louise; her Beast was an old bull whose pawings and snortings she could no longer endure. Meeting me had intensified natural need; it was lust at first sight.”

Now, the reader might feel as though a 1940s hardboiled film noir is unspooling. Certainly, the beautiful libido-driven dame in a bitter marriage to a wealthy, sexually repulsive older man, is straight out of the noir playbook. And Bloch doesn’t stop there with the subgenre imagery. Consider this passage lamenting the seedier aspect of L.A. at Christmastime: “I drove through dusk. Lights winked on along Hollywood Boulevard from the Christmas decorations festooning lampposts and arching overhead. Glare and glow could not completely conceal the shabbiness of sleazy storefronts or blot out the shadows moving past them. Twilight beckoned those shadows from their hiding places; no holiday halted the perpetual parade of pimps and pushers, chickenhawks and hookers, winos and heads. Christmas was coming, but the blaring of tape-deck carols held little promise for such as these, and none for me.”

Despite such despondency, the narrator and Louise do have fleeting moments of hope and joy. Since her marriage, Louise was unable to celebrate Christmas in her own home; her spouse took her with him on his business trips abroad during the season. When she believes she is rid of the offensive husband, she rejoices in the prospect of decorating the tree: “If you’ve ever gone Christmas shopping with a child, perhaps you can understand what the next few days were like. We picked up our ornaments in the big stores along Wilshire; like Hollywood Boulevard, this street too was alive with holiday decorations and the sound of Yuletide carols. But there was nothing tawdry behind the tinsel, nothing mechanical about the music, no shadows to blur the sparkle in Louise’s eyes. To her this make-believe was reality; each day she became a kid again, eager and expectant.” With this eloquent passage, Bloch not only reiterates the socio-economic contrasts of different parts of the city but also conveys a facet of Louise’s character that renders her more sympathetic. She is not merely a cheating wife, who attained a lavish lifestyle and regrets the price she’s paid. Bloch humanizes her and simultaneously sets up a harbinger for the horror that follows.

Robert Bloch was a supreme Horrormeister. His prolific career in the genre attests not only to his longevity in the field, but also his success in it. While I prefer his supernatural tales to the purely psychological ones, “The Night Before Christmas” impressed me with its ability to shock despite the inevitability of the plot’s trajectory. Bloch’s buildup to the denouement is utterly admirable in its artful construction. And his infamous gallows humor is on full display with the story’s killer last line. “The Night Before Christmas” is the literary equivalent of holiday counterprogramming, one of many gifts that Robert Bloch has given to horror fiction.